ESRR - On Metric Acronyms

Excitement -> Skepticism -> Reflection -> Resolution, or, my journey with metric frameworks

If you work on the growth or customer lifecycle teams of a digital product company, you’ve probably come across many acronyms that seem dubious at first. There is DAU, MAU, AARRR, HEART and more. As this article says: “AARRR stands for Acquisition, Activation, Retention, Referral and Revenue and is pretty much the bee’s knees when it comes to understanding your customers, their journey and optimizing your funnel as well as setting some valuable and actionable metric goals for your startup." Dave McClure from 500 startups coined this years ago.

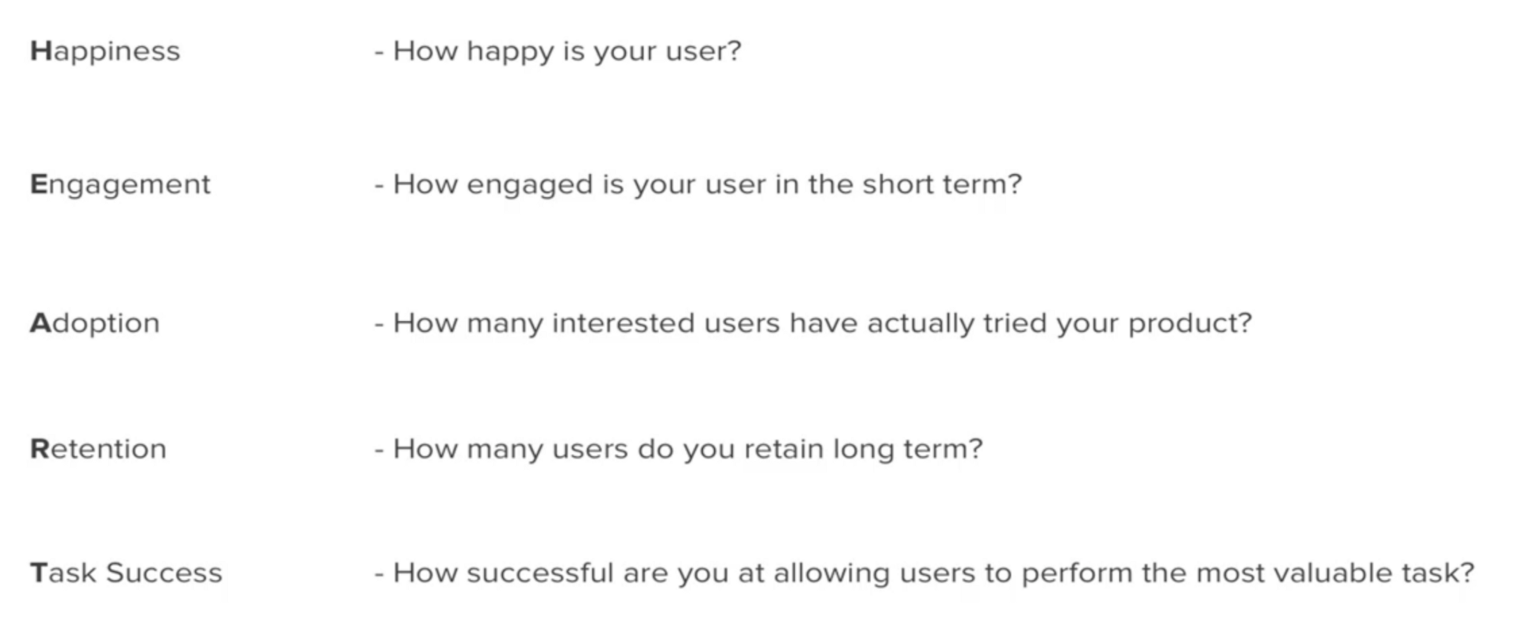

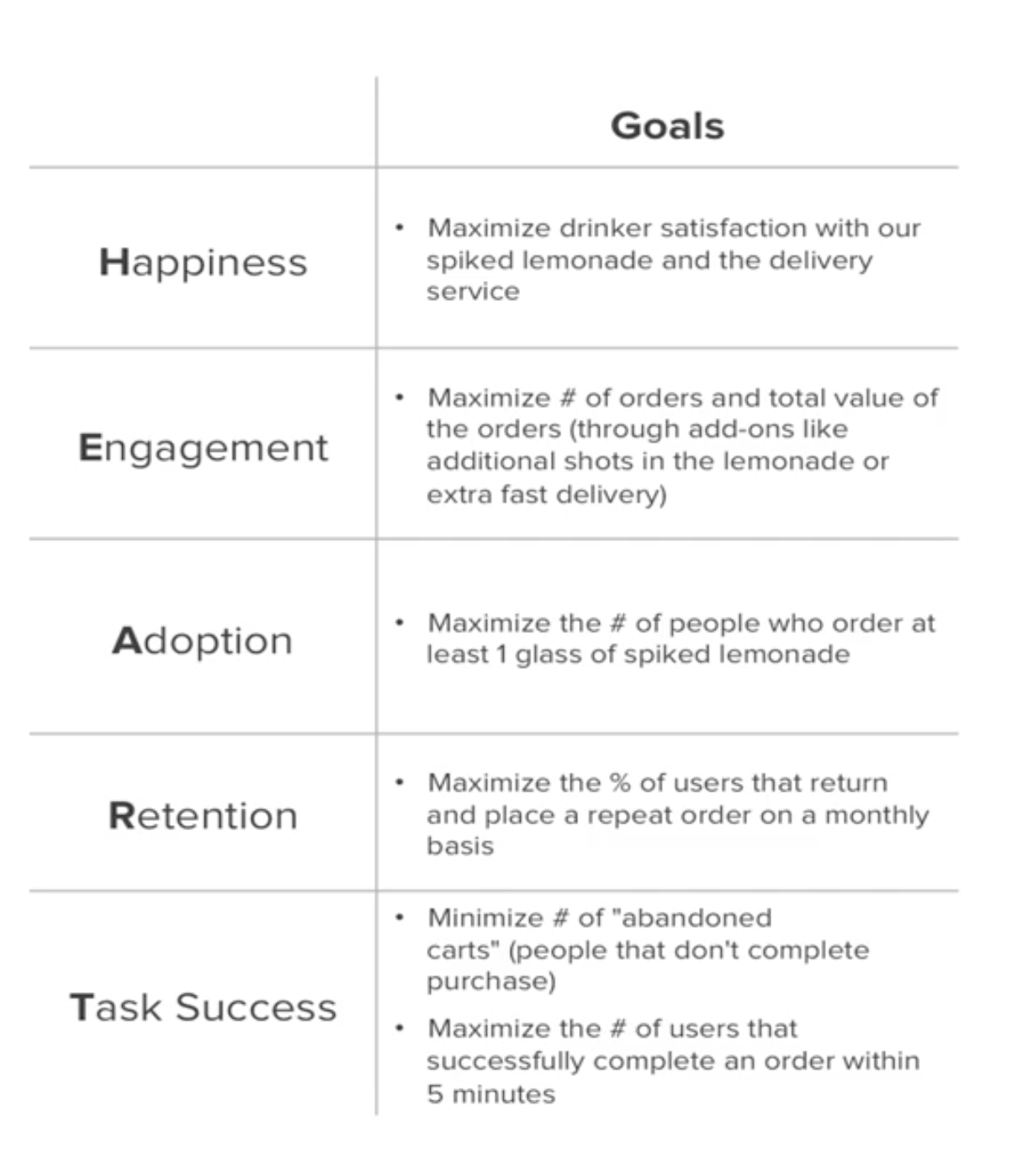

There is also the HEART framework by Kerry Rodden which stands for Happiness, Engagement, Adoption, Retention and Task Success.

In this excellent online class on Product Management, Cole Mercer applies the HEART framework to a lemonade stand :)

I once spoke to someone on the Facebook Messenger Growth team. They use the terminology of Acquisition, Activation, Engagement, Churn and Resurrection to think about their users’ lifecycle. AAECR? Not sure if they acronym it.

Clearly these are excellent frameworks to get started with quantifying your user’s journey.

But I think there are a few issues with these frameworks.

One, some of these words are creator-centric

Most of these words are “company-centered” or “creator-centered”. What we want our users to do. Are we “acquiring” enough users? (No, thank you sir I definitely do not want to be acquired). Are users engaging enough with our product? No, well then why don’t we send a couple more notifications? (Oh perfect, more shit to interrupt my day)!

In this TED talk Lera Boroditsky talks about how language shapes our thought. By using selfish terminology we might not always do what is best for the user. Teams are often asking “how do we increase engagement”? And that doesn’t always translate to great answers.

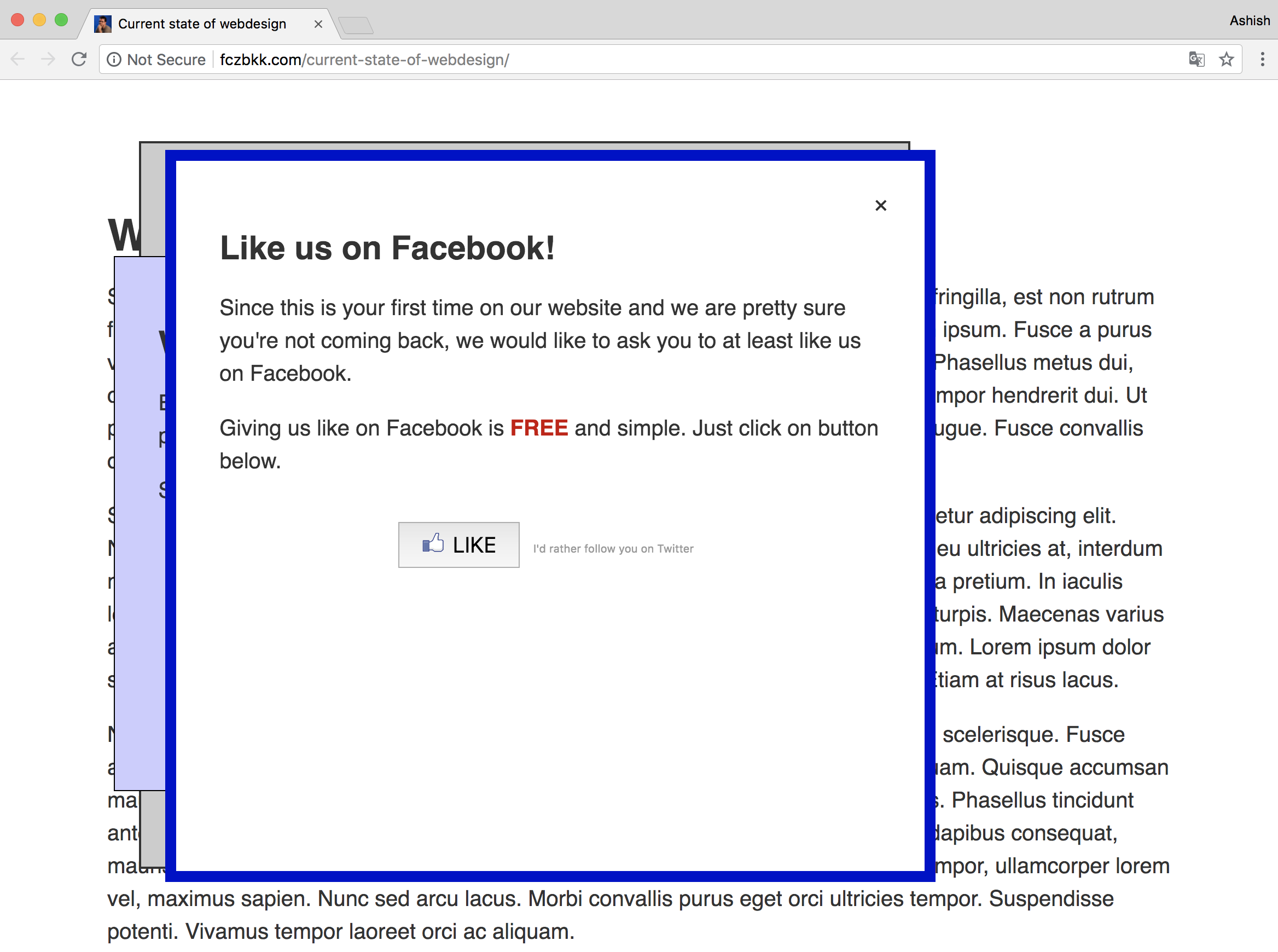

This website is a funny response to how websites these days are constantly asking to you subscribe to browser notifications, subscribe to a newsletter and more.

Why? Well, if you opt-in, they can presumably send you triggers to engage more with their product.

Imagine products that do not come with a comms channel. Perhaps a good old physical notebook. Here, the creator does not have a way to nudge a user. The triggers to “engage” with a product are shaped by a user’s life. If you are a writer, you would write regularly and might go through a notebook each month. (A product manager would call this user highly “engaged”). If you just graduated from school you might not use them as much anymore. (These would be “churned” users in need of “resurrection”). There is little you can do here as a creator to change engagement. Why not let the consumer’s life shape the engagement instead of you shoving it down their throats again and again?

Two, they are too generic

What does “engagement” even mean? Zomato, a company I worked for in the past offers three very different services. You can use Zomato to find a place to eat, perhaps when you are in new city or neighbourhood; you can order food for delivery; you can reserve a table. Now just think about how often and how long one might do these things, depending on the nature of the service and the context of the user. If you just started dating, you might check restaurants regularly, and on occasion even need to reserve some of them (the ones that are hard to get in to). If you just moved out of your hometown for a job, you are probably ordering in a lot. For restaurant discovery, you might use the feature a lot once you move to a new city, and later use it occasionally.

“Good” engagement numbers would be different for all of these scenarios. But it is possible that you might consider one perfectly happy user less engaged. What is the right terminology to user in this context of use? Devoid of specificity, engagement just boils down to “how do we get our users to open the app again?” or “Once they open the app, how do we increase the time they spend in the app?”. But these questions are too generic. They create the worst kind of product tweaks.

Three, they come with incorrect expectations attached to them

Andrew Chen, one of the experts in the field of product growth, wrote this essay recently.

He writes:

DAU/MAU is a popular metric for user engagement – it’s the ratio of your daily active users over your monthly active users, expressed as a percentage. Usually apps over 20% are said to be good, and 50%+ is world class.

He adds:

Not everything has to be daily use to be valuable. On the other side of the spectrum are products where the usage is episodic but each interaction is high value. DAU/MAU isn’t the right metric there.

But if you haven’t read this essay and you read somewhere that you need to be over 20% to be good, you might adopt strategies that are incorrect for your product. People might already be using your product at its “natural” frequency and retention.

Yes, these are starting points…

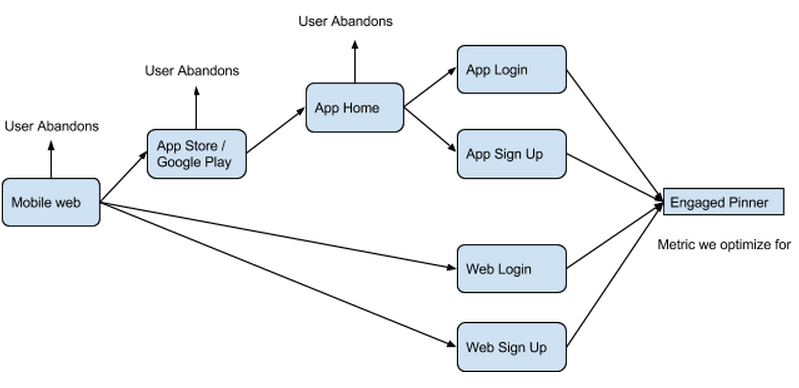

I realize these are starter frameworks, and companies are way more sophisticated than that. Here’s an excellent case study how Pinterest designed metrics for mobile growth. They are optimizing for “engaged pinners”. And, they are recognizing trade-offs and using multiple metrics to find the right balance.

But many companies, especially the young ones, might not have evolved their tools to do this. Most ready-to-use analytics softwares come with the same standardized metrics.

What do to?

I don’t know yet. One idea I was prototyping was to come up with your own acronyms. Find user-centered words that are specifically describe their journey with your product and design for that!